Space is big.

It’s also cold and unforgiving. While unforgiving is certainly a term that can be leveled at Out There, Mi-Clos Studio’s game certainly isn’t cold. Bleak? Sure. Melancholy? Certainly. But it’s also a game with plenty of heart in it, with everything from its pulp-sci-fi art style to a streak of wicked humor cutting though what is an oppressive - yet addictive - experience.

Set in the 22nd century, you awake from a cryogenically-induced slumber to find yourself floating in an unknown area of space. Your goal is to locate additional resources and take them back to Earth, which has been stripped bare. Your only initial goal is indicated by a red arrow pointing you in the direction of a distant planet. Over time, your interactions with others will throw up additional objectives. How you get there is up to you. Whether you get there, however, is a different matter entirely.

Taking its cues from FTL: Faster Than Light, Out There is a randomly-generated sci-fi RPG which requires you to carefully juggle your available resources as you explore the galaxy. You’ll roam from planet to planet, mine planets for their resources, converse with alien races (or, at least, attempt to), and install new systems.

Every action you take comes with a cost, however. Traveling consumes fuel and oxygen, and random events are triggered between your movements which could see your ship repaired, damaged, or you could learn or forget how to build various ship components. You can harvest more oxygen from Gas Giants using probes, but doing so damages your hull and those probes come with a fuel cost of their own. With no way of knowing how many resources you’ll obtain before you launch a probe or land on a planet, every action you take has a risk attached to it. Run out of fuel, oxygen or find your hull integrity reduced to zero, and it’s game over. Do you expend precious fuel in order to mine a planet for resources that will let you improve your engine’s efficiency, or do you attempt to increase your fuel reserves, knowing that your ship could suffer huge damage in the process?

Die, and you have to start over - there’s no option to save your game. While this may sound frustrating, it adds to the tension.

Thankfully, your ship comes with a cargo hold, divided into slots and allowing you to carry excess resources. Space is limited, and any new technology you obtain along the way will occupy a spare slot; but that new technology could reduce the amount of fuel you expend on your travels, or increase your ship’s durability, allowing you to survive just a little bit longer. You’re also able to find abandoned ships and take those over, and often they come with advanced technology already installed that you may not have learned how to craft yet - such as the ability to travel through wormholes, terraform planets to support life, or even collapse stars and create a black hole.

You’ll also come across various planets housing alien life. Landing on these will replenish your oxygen reserves and allow you to interact with the inhabitants. Initially you can’t understand a single word they say, but over time you’ll start to piece together enough of their language to enable you to gain more resources or new technology from them.

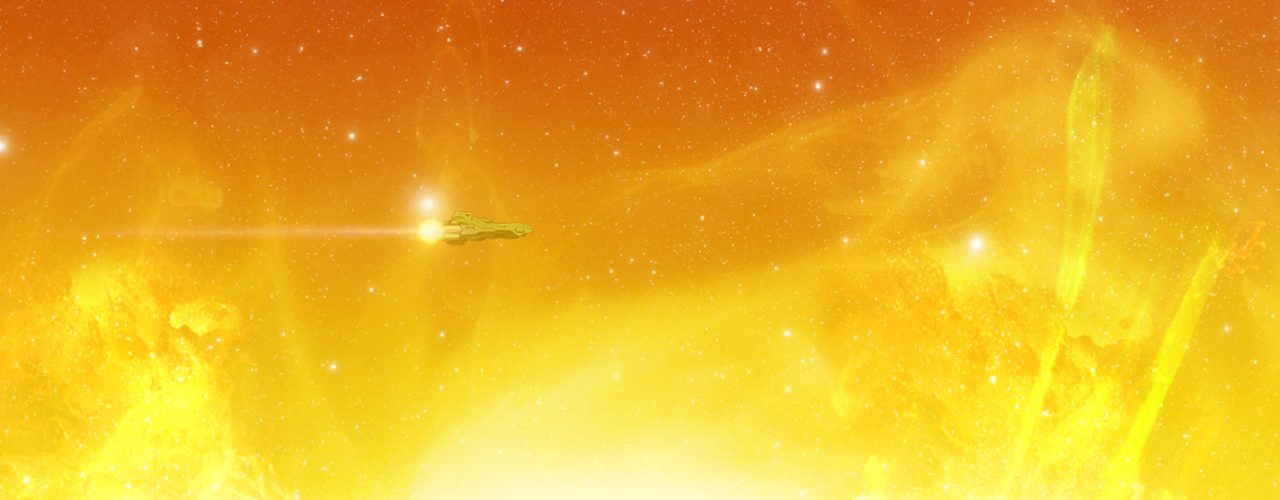

All of this takes place against a backdrop of pulpy sci-fi artwork evoking 1950s movie posters and comic books. Thick black lines surround everything, colors are bright and bold rather than the desaturated hues so familiar from modern sci-fi, and while the animations fall just short of being non-existent, the game is gorgeous to look at - though it’s safe to say that it won’t be to everyone’s taste. The soundtrack meanwhile is a constant background ambiance of synth instruments, which reinforce the sense of isolation and loneliness. It’s not exactly something you’ll tap your feet along to, but it’s certainly atmospheric.

In addition, the game’s script - while not without some spelling and grammar errors - does a good job of both conveying the feeling of being a small fish in a very large pond, and even manages to slide in a few moments which will have you smiling in amusement. There’s times where it overdoes things with passages musing about the futility of life, or whether humanity is worth saving, but by and large the writing is strong and meshes well with everything else the game has to offer.

As with FTL, the urge to start another playthrough is strong. After close to 50 games, it’s quite likely that you’ll still be coming across new things - whether those are random events, new ships or technology. The urge to start a new game immediately after failing a previous one is strong.

However, the knowledge that you’re always at the mercy of a roll of the dice can annoy. You’re making choices, but you’re doing so without full knowledge of the outcome. The game’s systems are complex, but even upon fully understanding them you never feel in control, or that your understanding actually makes a difference to your chance of survival. Sure, you can find technology deep into the game which will allow you to see what resources a planet holds before mining it - but that’s obviously dependent upon whether you manage to survive long enough to obtain it in the first place.

Ultimately, Out There is a game which can initially confuse with its complexity - and frustrate through its randomness - but it’s all too easy to sit down for five minutes before finding yourself still playing over an hour later. Despite its faults, the game is a satisfying slice of roguelike fun on the move. And with its beautiful art style and atmosphere, it’s easy to fall in love with - even when it feels as though success is ultimately outside of your control.