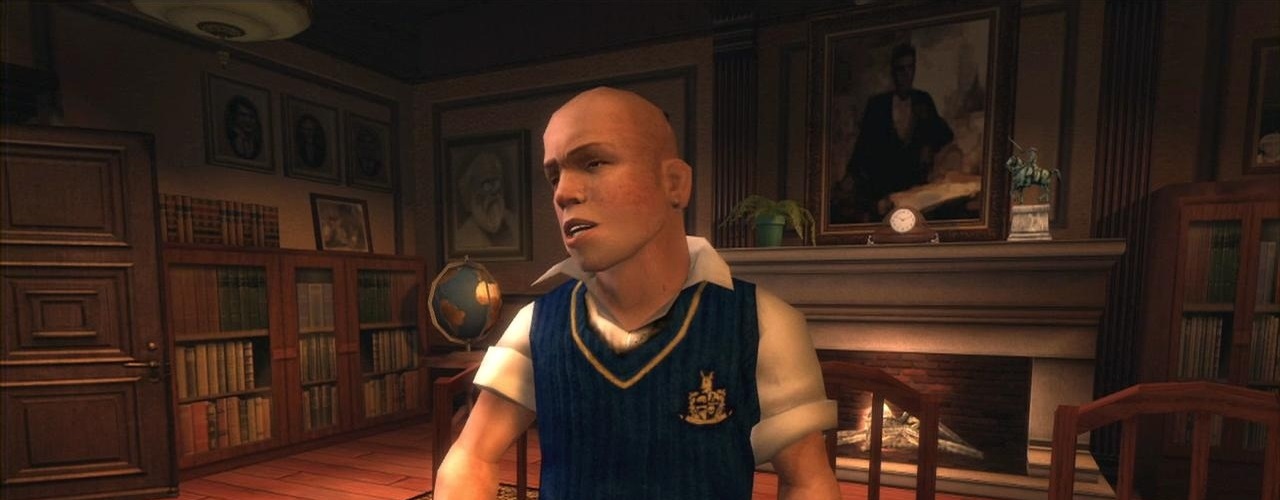

“Hey Jimmy Hopkins, what are you rebelling against?”

“Whatta ya got?”

Nostalgia is a funny thing.

Whole industries obsess over it, drumming out new products, new ads, new slogans, anything to make you feel a twinge of… what exactly? Regret? A fleeting instant of reliving something poignant, something powerful—déjà vu incarnate.

Troublesome for the marketing industry, then, because the best moments of nostalgia always hit you from out of nowhere.

There is such a moment in Rockstar’s Bully. After Jimmy Hopkins arrives at his New England boarding school, and you guide him through the obligatory meet-and-greet of major characters and opening missions, the gates of Bullworth Academy open wide, and you’re freed to explore the town.

For just a second, there’s a sense of childlike abandon as you whip your bicycle over the bridge and into town, careening head-long past oncoming cars and causing pedestrians to yell angrily at your hooliganism. Somehow, Rockstar captures the feeling every kid feels upon getting their first bicycle. Your world is no longer dictated by stern-faced adults with their stuffy notions of “child safety”—you can just jump in the saddle and go. You are mighty.

The moment itself is not entirely unique—every open-world game has a point where it cedes unrestricted access to its world over to the player, after all—but in Bully, we experience that cleaving of authority through the eyes of an angst-ridden teenager. And not just any embittered teen, either; the very first scene of the game has Jimmy sprawled in the back of his mother and adoptive-father’s car, clearly resentful of every second he has to spend in their company.

“What, who are you?” Jimmy demands when his new dad rebukes him. “Mom, I thought you told me never to talk to strangers.”

To smart-alec Jimmy, Bullworth academy is just one more institution where his dysfunctional family can dump him.

The physical world of Bully is smaller than its counterparts in Grand Theft Auto (fictionalized New York City, Miami and California), or Red Dead Redemption (the American Old West), but it feels somehow more expansive. Because the scope of the world is narrowed to the experience of one 15 year-old, it feels richer and wider - like there is a point to exploring every nook and cranny.

That sentiment is only aided by just how strange a world Bullworth actually is. The whole town - and everything in it - seems to be slightly off-kilter, underscored by a jarring, tinkling soundtrack. As you ride down the street, you pass jocks throwing nerds’ homework in the air, greasers strutting about like peacocks stuffed into leather jackets, and preppy kids faking British accents to give allusions of wealth and status. It’s an eerie microcosm of Americana—Grease meets The Stepford Wives by way of Animal House.

Back to my point about nostalgia being a funny thing. Nostalgia hits each of us in different ways, no matter how hard any art form tries to tease it out of our subconscious. For me, that moment came while playing Bully.

I grew up in towns like Bullworth. The feeling of the seasons—the rain of bright leaves in autumn, the cold leadenness of winter, and the bright burst of spring all translate brilliantly through little touches in the game. Even in the game, winter seems to drag on abnormally long (possibly thanks to some extra missions in the Scholarship edition).

It would be impossible to say that any one town is exactly like Bullworth. You could drive all over the American northeast, and I’m sure you’d find dozens of little towns that matched the basic description, but none that matched it for sheer variety of oddball characters (I have yet to meet a drunken Santa).

What’s more important is the idealized vision of New England that Bully presents—of wealth and status, yacht clubs and cucumber sandwiches. Racing down the street to the dilapidated carnival after class actually became one of my favorite pastimes in the game. Bully, replete with a Halloween night of epic pranks in the school itself, manages to capture what every boy dreams their childhood might have been like.

That’s important, because what Bully pulls off best is how it subverts the ritz and glamour of the 1%’s playground. Look closely enough at the cracks in the town of Bullworth, and you quickly start to realize things are never as cheerful as they appear. When you first see Bullworth Academy, the place is more than a little run down—old paper blowing about, windows in disrepair.

You don’t have to go very far into town to see that the wealth and prosperity of Bullworth Academy’s “great name” has not reached everyone. Despite all the controversy surrounding their titles, Rockstar games rarely gets credit for how well they portray the daily realities of economic inequality in their games. Both sides of the coin are so wonderfully caricaturized, it’s really hard not to laugh at it all sometimes.

In truth, that’s probably the most nostalgic part of playing Bully. It’s a running theme throughout New England that where you have wealth, you also have poverty. Go to a small town in the northeast, and you can actually find Gatsby-esque clubs and parties, but you also won’t have a hard time finding slums and ghettos either. Somewhere in the middle is Jimmy Hopkins rushing around on his bicycle, flush with adolescent freedom, laughing at the world like it’s all a great big joke.