I played Metal Gear Solid 4 well before I had a PS3 of my own. At the time, it was the only game on the system that I was truly interested in playing. My excitement leading up to its release inspired me to buy the Metal Gear Solid Trilogy released for the PS2, which I then traded with a friend after he bought the MGS4/PS3 bundle. I had the game/system for a long weekend while he gave himself a franchise refresher.

I ended up playing the entire game with a different friend by my side. He would point things out that I had missed, but he didn’t ask for the controller; he was happy being a passive observer. Even so, there was one moment where I gave him the controller, because I physically couldn’t play anymore. The moment in question comes late in the game: Old Snake is broken and beaten, and he’s trying to stagger down a hallway that is covered in microwave emitters that are heating up to deadly temperatures. It’s a fascinating scene in and of itself, but what makes it unique is the way it involves the player in Snake’s suffering.

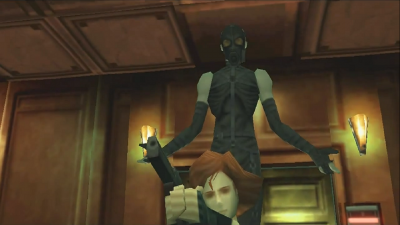

The Metal Gear Solid series has always had a fascinating relationship with the fourth wall. Snake is his own character, but while he is not “aware” of the player, he acts as a sentient representation of the player. You may think that that’s technically true for every videogame character, but not the same way it is here. When Psycho Mantis messes with Snake in the first Metal Gear Solid, he’s not messing with Snake; he’s messing with you, the player. Even though he is ostensibly talking to Snake, he isn’t telling Snake what games he likes. He’s telling you, the player, what games you like, based on your memory card data. He stops being able to read Snake’s mind because you, the player, change controller ports. The message you receive in-game that says “Plug your Controller into Controller port 2” is not to Snake but past him, to you (the player).

The Metal Gear Solid series has always had a fascinating relationship with the fourth wall. Snake is his own character, but while he is not “aware” of the player, he acts as a sentient representation of the player. You may think that that’s technically true for every videogame character, but not the same way it is here. When Psycho Mantis messes with Snake in the first Metal Gear Solid, he’s not messing with Snake; he’s messing with you, the player. Even though he is ostensibly talking to Snake, he isn’t telling Snake what games he likes. He’s telling you, the player, what games you like, based on your memory card data. He stops being able to read Snake’s mind because you, the player, change controller ports. The message you receive in-game that says “Plug your Controller into Controller port 2” is not to Snake but past him, to you (the player).

But this isn’t about the Psycho Mantis fight in Metal Gear Solid, as brilliant as that is. It’s also not about breaking the fourth wall (not really). It’s about feeling. And to talk about feeling, let’s talk about a game that doesn’t have much of it: Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

The most significant scene in Infinity Ward’s extremely significant first person shooter comes in the immediate aftermath of a nuclear explosion. Your character was in the blast radius, and you get to experience his last few moments as he slowly crawls around, surveying the wreckage of a now-leveled city. Problem is: there’s no sense of presence. You don’t feel like you’re in this horrific situation; you don’t feel like anyone is in it. Because in Modern Warfare, you’re nothing but a camera. And in the moments where the floating gun with fake arms attached to it disappears, you’re left with nothing to connect to.

The game’s opening scene was every bit as problematic. You have no control over your character, you don’t know who he is or what he did, but at the end of the sequence, he is shot in the face. This all happens in first person, so when the game cuts to black after that bullet is fired point blank, it’s a shocking moment. But it isn’t an effective one, because not only is the “character” not real in our world, he’s not real in his fake one either.

Before the execution, you are forced into the backseat of a car. You can’t move, but you can look around. On either side are guards and out the windows are hordes of angry people. But what are they angry about? Who are they angry at? It’s impossible to say, because below you is nothing. Just the seat. There’s no body. You are controlling a fixed camera on an invisible tripod. And while I can feel for a simulated person, my empathy for cameras – real or imagined – is pretty limited, so shooting one in the lens isn’t really going to affect me.

Before the execution, you are forced into the backseat of a car. You can’t move, but you can look around. On either side are guards and out the windows are hordes of angry people. But what are they angry about? Who are they angry at? It’s impossible to say, because below you is nothing. Just the seat. There’s no body. You are controlling a fixed camera on an invisible tripod. And while I can feel for a simulated person, my empathy for cameras – real or imagined – is pretty limited, so shooting one in the lens isn’t really going to affect me.

With no visible arms grasping the desolated earth in front of your post-Nuclear “body,” there’s a similar lack of presence. You’re doing little more than controlling a Nuclear Exploration Rover from the safety of your couch. You’re not there, and neither is anybody else. It’s a visually striking scene, but it’s ultimately meaningless.

Imagine if your character had a body, though, and as you/he “crawled” around the wreckage, you could the immediate impact of radiation poisoning appearing on his charred skin. That would create a sense that this was a person suffering and not just a slow moving camera eventually running out of battery. You, the player, would not actually be suffering, but the feeling of presence (even someone else’s would heighten the impact. And the mild frustration of controlling this futile figure would be mitigated by the legitimate shock factor and the ensuing empathy/revulsion). It would turn an interesting moment into an affecting one.

But it’s not enough just to see the body. About two-thirds of the way through The Last of Us, Joel, the player character, is badly wounded by a fall. When he gets up, it leads to an interesting few minutes of gameplay, unlike any other part of the game. As Joel staggers forward, the camera swings about and the screen fades in and out. You’ve lost total control of Joel in much the same way that you lose control of drunk Nico Bellic in Grand Theft Auto IV. And here you can feel empathy for this character, because you’ve spent time with him and you can see his suffering. But instead of feeling that suffering, you just feel frustration. You and he have the same goal (“Don’t die”), but he is terrified and you are annoyed by how suddenly difficult he is to control.

To make you truly feel pain, the game has to cause pain. And MGS4 does that with its control method during the microwave hallway. Rather than it’s something else entirely. (As is the game’s final fight, which incorporates a completely new control scheme between two 40+ minute cutscenes… but that’s a whole other article in itself.) Getting Snake down that hallway requires you, the player, to rapidly press the triangle button for its entire duration, and it’s a long hallway. Snake’s clothing started to break and his skin began to smoke as my hand started to hurt only halfway through.

By the three quarter mark, I couldn’t take it anymore. I handed the controller off to my friend and had him finish the sequence for me. As he hammered the button and I massaged my wrist, I stared at Snake and felt an actual physical connection to him. I may not have been burning alive, but he and I both hurt. I was every bit as relieved as he was when he reached the other side. It was over.

For both of us.